Topics: Οργανωσιακή Θεωρία και Συμπεριφορά (Organizational Behavior), Επιχειρηματικότητα (Entrepreneurship), Εταιρική Κοινωνική Ευθύνη (Corporate Social Responsibility), Strategic Management, Leadership , Organizational Culture and Change

https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries?cid=other-eml-alt-mgi-mck&hdpid=1cfa80cb-a39d-4a6d-9137-edf6787e862f&hctky=11703013&hlkid=aa1bb300011d4c91ac0965d3ed10ca77

"Technology has helped make life tolerable in the pandemic. And whenever it becomes normal again to leave the house for work, school and shopping, we won’t be going back to the way it was. What were conveniences before the pandemic now seem necessities that we’re unlikely to give up even after there’s widespread immunity to the coronavirus. And there are a number of reasons this new stay-at-home economy will likely be an important part of the new normal.

First, companies have made huge investments in the infrastructure needed to deliver goods and services to our homes quickly and efficiently, which means those products are now easier to use and often less expensive. Second, families have also invested in the services and gadgets to keep their members safe and sated while sheltering in place. Third, our habits have changed: Many people have gotten over the “hump” of adopting new technologies earlier than they otherwise might have. And finally, hundreds of thousands of Americans who lost traditional jobs in retail and service—on showroom floors and inside restaurants—have found new ones working in online order fulfillment and delivery. Even those who retained their jobs are seeing their roles shift to address these new conduits for economic activity."

Work-from-home employees whose days seem longer, with more meetings and emails than ever before, may find a new Harvard Business School study validating.

An analysis of the emails and meetings of 3.1 million people in 16 global cities found that the average workday increased by 8.2 percent—or 48.5 minutes—during the pandemic’s early weeks. Employees also participated in more meetings, though for less time than they did before COVID-19 sent many workers home.

“There is a general sense that we never stop being in front of Zoom or interacting,” says Raffaella Sadun, professor of business administration in the HBS Strategy Unit. “It’s very taxing, to be honest.”

Shifting to remote work at the start of the pandemic stripped away whatever was left of the elusive 9-to-5 business day and replaced it with videoconferencing and “asynchronous work.” With at least 16 percent of Americans planning to keep working from home part of the time after COVID-19 abates, researchers are probing how virtual interaction might reshape organizations.

In the first large-scale analysis of digital communication early in the crisis, the team—Sadun; Jeffrey T. Polzer, the UPS Foundation Professor of Human Resource Management; HBS doctoral candidate Evan DeFilippis; New York University doctoral student Stephen Michael Impink; and former HBS research associate Madison Singell—studied aggregated, anonymous emails and meeting invitations of employees at 21,500 companies in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.

“THERE IS A GENERAL SENSE THAT WE NEVER STOP BEING IN FRONT OF ZOOM OR INTERACTING. IT’S VERY TAXING, TO BE HONEST.”

“The role of an office is to congregate and help people work together,” Sadun says. “For us, the question was, ‘What happens when you cannot have that physical space anymore?’ How do people adjust their work patterns?”

The team compared the frequency and timing of emails sent within and outside organizations eight weeks before the start of pandemic-related lockdowns and eight weeks after. On average, they found that:

Sadun and Polzer also analyzed meeting invitations—the quantity, duration, and number of attendees—and observed that:

Perhaps most striking: As researchers compared the time when people started sending emails and attending meetings each day and when they ended, they saw that the average workday lasted 8.2 percent longer, an extra 48.5 minutes. While it’s unlikely that employees worked continuously during that period, Sadun suspects that employees adopted more fluid schedules to accommodate interruptions from, say, a child struggling with virtual learning or a sick family member.

“Unless you really are able to create distinct boundaries between your life and your work, it's almost inevitable that we see these blurring lines,” she says.

The research team detailed their findings in the working paper Collaborating During Coronavirus: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Nature of Work, released by the National Bureau of Economic Research in July.

The anonymized nature of the data made it difficult to discern the quality of the meetings and email communication, and the impact on employees’ well-being. The study also didn’t include the time spent on collaboration tools, such as Slack and Microsoft Teams, which have become increasingly popular.

To tackle some of these questions, Sadun has been studying how 300 knowledge workers have been spending their time during the pandemic and how those activities affect their moods and perceived effectiveness. So far, the preliminary conclusions have been highly varied and personal.

“This is one of those things where it’s hard to make one statement for everybody,” Sadun says. “If you have a large house, life is good. If you have to combine your bedroom with your office, it’s not as good.”

It doesn’t take a detailed time log to know that videoconferencing fatigue has long set in for many employees, a likely factor in shrinking meeting times. Gathering in person doesn’t seem as draining as staring at a screen.

“The issue with Zoom is that you’re always on there. You have to show a concentrated face the whole time,” she says. “It's very unnatural to be constantly looking attentive for hours.”

The pandemic workforce has created a significant challenge for managers, Sadun says. She offers three pieces of advice to leaders of remote workforces:

Sadun, who spent the spring advising the Italian government about how to reopen its economy post-lockdown, hasn’t been immune to the pandemic’s disruption. But, for an academic analyzing a once-in-a-century pandemic and its economic fallout, working has been a way of coping.

“This is our way to make sense of the world,” Sadun says. “We try to make ourselves useful because we understand that there is something really big happening around us.”

Danielle Kost is senior editor of Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.

[Image: iStock Photo]

https://www.theverge.com/platform/amp/2020/11/8/21553014/virgin-hyperloop-first-human-test-speed-pod-tube?utm_source=morning_brew

https://www.strategy-business.com/article/Best-Business-Books-2020-Management?gko=16c0a&utm_source=itw&utm_medium=itw20201111&utm_campaign=resp

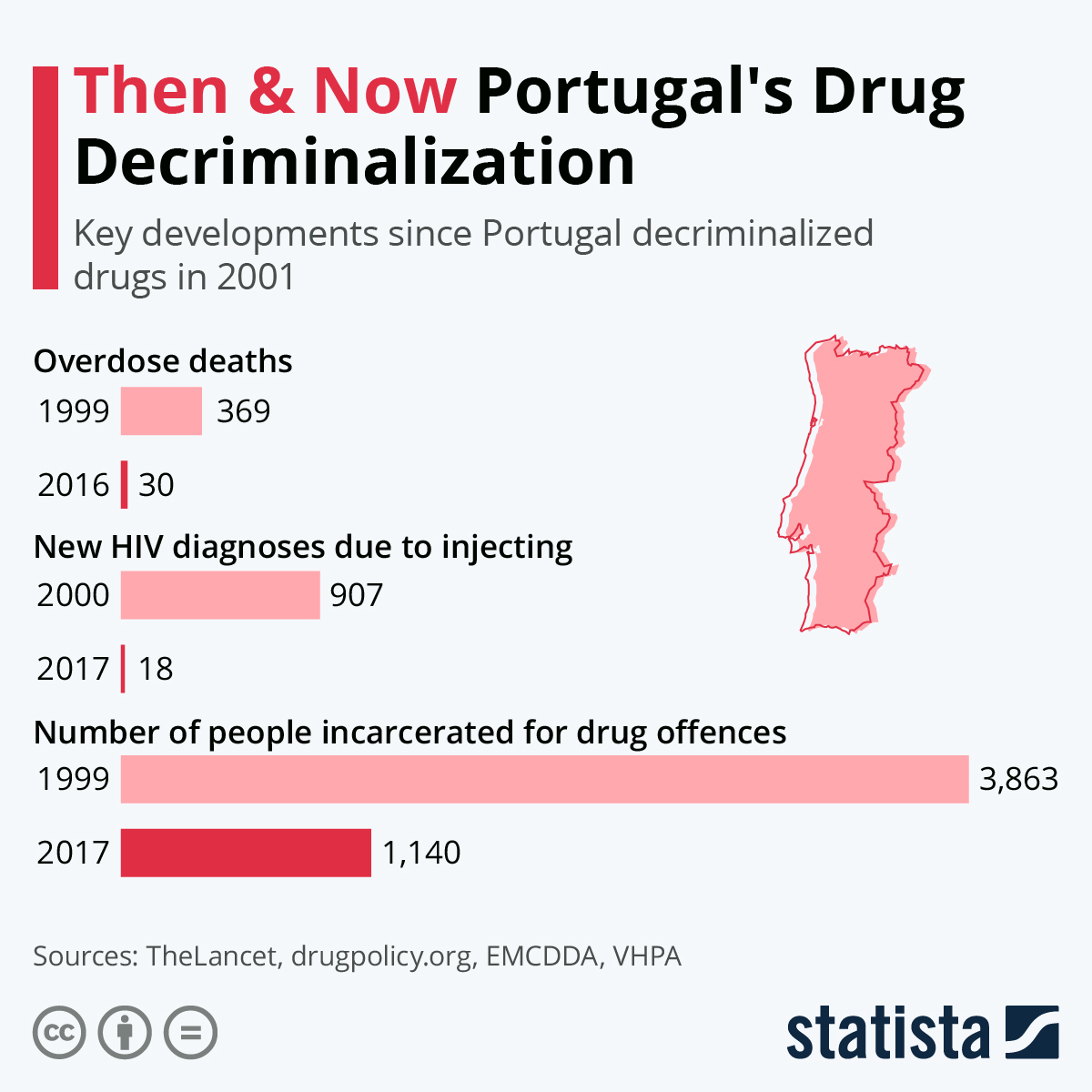

During the 1990s, Portugal was devastated by a drug crisis where one in every 100 people became addicted to heroin and the rate of HIV infection soared to become the highest in the European Union. Portugal's radical move to put an end to the carnage should prove an example to other countries dealing with similar problems, especially the United States where opioids have killed more people than the totality of American military casualties in Vietnam, both Iraq wars and Afghanistan combined. That move was decriminalizing the consumption of all drugs and Portugal became the first country to do it.

The policy saw the status of using or possessing drugs for personal use remain illegal. However, offenses were changed from being criminal in nature which involved prison as a possible punishment to being administrative if the amount possessed was no more than a ten-day supply. Needle exchange programs have also been in place since 1993 and today, all drug users can exchange syringes at pharmacy counters across Portugal. Drug treatment was also expanded and improved with successful results.

Finding historical data highlighting the severity of the addiction problem during the late 1990s is difficult but some important numbers do exist which help to show just how remarkable Portugal's recovery has been. The following infographic pulls data together from several sources to illustrate some key developments. Back in 1999, Portugal experienced 369 overdose deaths and in 2016, the number was just 30. The number of new HIV diagnoses due to injecting has plummeted from 907 in 2000 to 18 in 2017. The new laws have also had an impact on incarceration with the number of people behind bars for drug offences falling from 3,863 in 1999 to 1,140 in 2017.

https://www.ibm.com/thought-leadership/institute-business-value/report/hr-3?utm_medium=Email&utm_source=Newsletter&utm_content=000038GP&utm_term=10012001&utm_campaign=PLACEHOLDER&utm_id=externalideawatch&cm_mmc=Email_Newsletter-_-Audience+Innovation_Innovation-_-WW_WW-_-externalideawatch&cm_mmca1=000038GP&cm_mmca2=10012001&cm_mmca3=PLACEHOLDER

https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/todays-skills-tomorrows-jobs-how-will-your-team-fare-in-the-future-of-work?cid=podcast-eml-alt-mip-mck&hdpid=b36c2373-2485-41ee-aff7-7ff12a546cf0&hctky=2920544&hlkid=b93250f307a2481a9733e11edf64a735